12 Angry Jurors: The Theater’s Roar for Justice

May 15, 2023

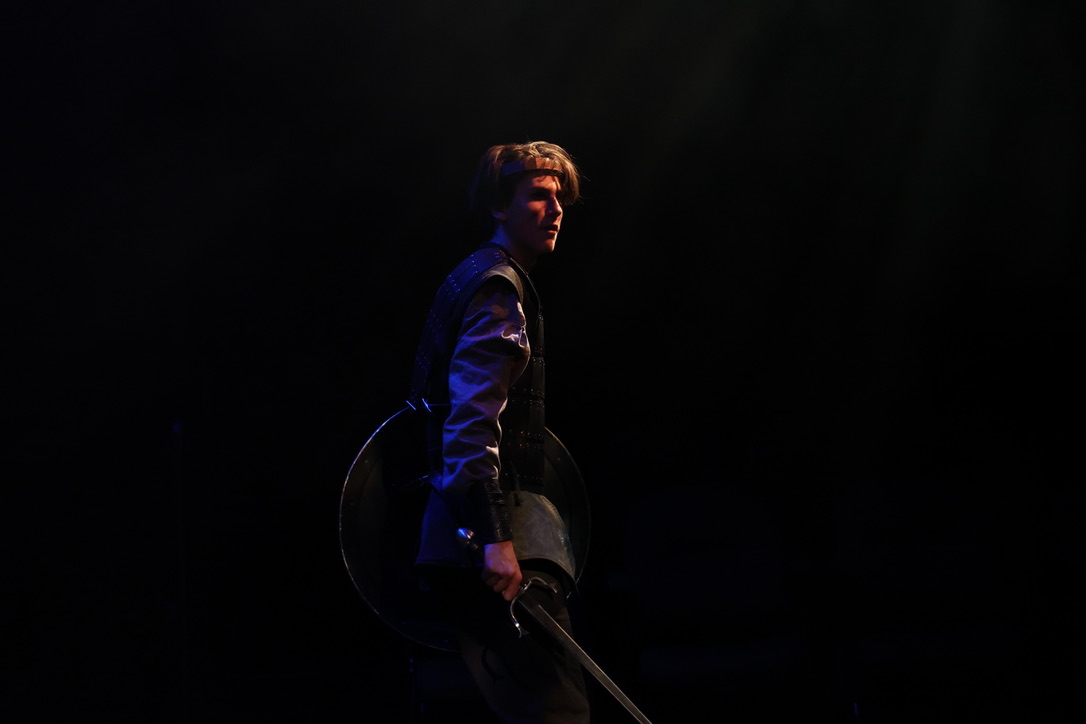

As the lights dimmed onstage in the Schoolhouse Theater, the third act of LuHi’s production of 12 Angry Jurors came to an end. An end to the story that our theater department took the time to study, memorize, and perform for us. This story, one which begs many questions, details the jury deliberating the guilt or innocence of a young boy on trial for his father’s murder. As the audience, we were invited along to explore not only the evidence at hand, but also the consequences and implications that our criminal justice system imposes upon everyone in American society. Yeah! It’s a heavy one.

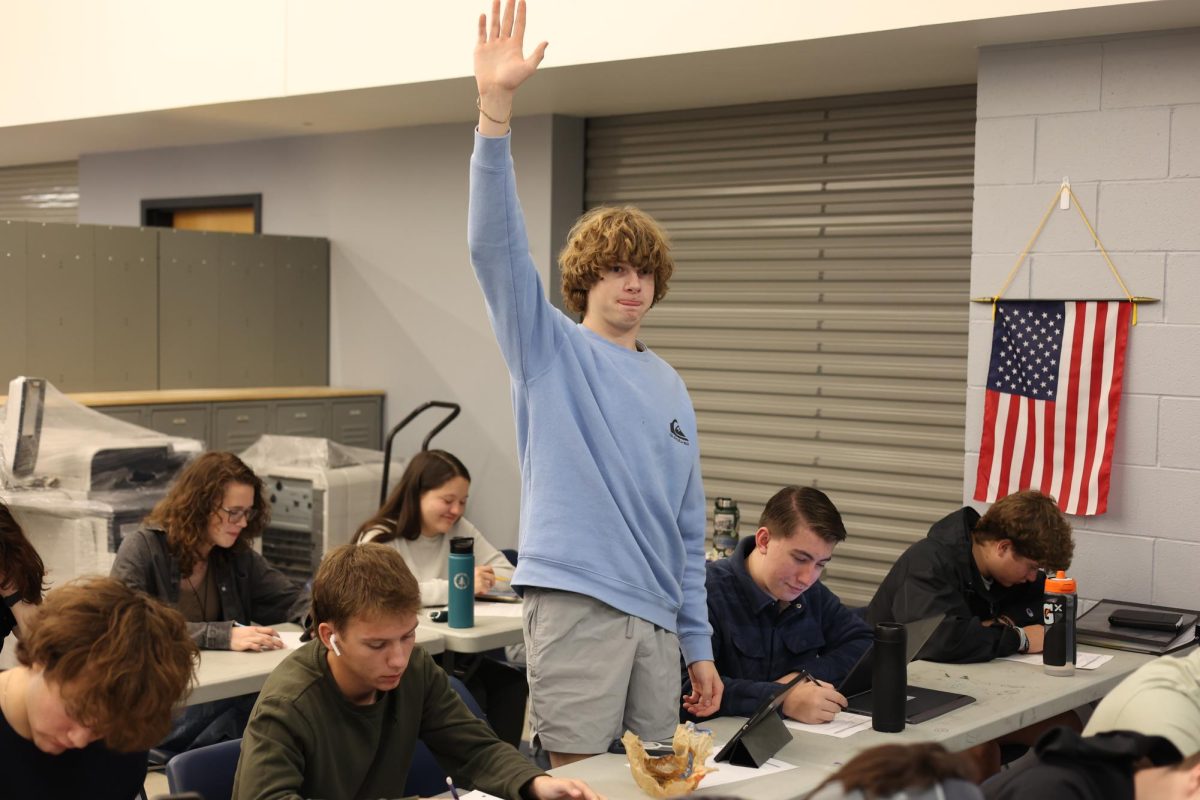

The play begins with a jury of 12 nameless characters entering the deliberation room, complaining about the summer heat, the waste of their time, and their complete desire to go home. The jury clearly contains a variety of people: some old, some young, some rich, some poor, some native, some immigrants, some apathetic, and one with compassion. After the first few minutes, it quickly becomes clear that this jury has one member who isn’t convinced of the boy’s guilt and is willing to fight for it. Throughout the play, Juror Eight spends the night convincing the other 11 jury members that declaring the boy guilty would be injustice. Declaring him guilty would be to ignore the principle of “reasonable doubt”. As the jury spends the next three acts deliberating back and forth, the audience gets to see them recount all the evidence, make arguments for or against, and beg questions about the humanity of our justice system and those involved.

To start, Juror Eight has to convince various jury members that their votes do matter. He manages to convince Juror Nine that their deliberations are not for nothing, which then allows him to present his case further. As Juror Seven repeatedly complains, they are going to spend their whole night here if they don’t agree, so why can’t Juror Eight just vote guilty and go home? But the audience is continually asked the question, “What is the cost of one night for the 12 of us compared to a lifetime for the boy? His lifetime in prison? His lifetime ended in the chair?” Throughout the entire play, this question comes up again and again, and remains central in the mind of the audience. Even though Juror Seven, among others, comes around at the very end of the play, others in the jury also continue to ask this question, even to the very end.

Another question that the play asks its audience is that of prejudice. Frankly, the human condition makes it impossible for us to completely remove our biases from our minds and judgments, especially in court cases. In my mind, Jurors Ten and Three embody prejudice very well, very much in line with what we think prejudice is. Juror Ten never once discusses the case, shouting in every instance about “them” and how “they” are. In one of the most memorable moments of the show, he rants about how crime and murder lie in “their” blood, that “they” are always going to be criminals. As he does so, the other members of the jury get up and face away from him, refusing to listen. No one uttered a single word, yet volumes were spoken in this memorable moment of silence. Juror Three also clearly shows that his emotions are involved more than his head, going off about his own son and “kids these days” and how they need to be punished severely. By the end of the play, it is clear that he considers the boy on trial to be a reflection of his own son, who needs to be disciplined. But prejudice takes many forms. Juror Eleven is an immigrant from an Eastern European country, who continually mentions the admiration and love she has for the American system. Because of this, she is likely (if not certainly) blinded by its shortcomings and injustices. Juror Five comes from the same background and neighborhood as the boy on trial, and although his initial vote is guilty, it doesn’t take much for him to waver and flip his vote. Juror Two is unable to provide her own reasons for her vote, even when she changes it later. Throughout the play, she votes on her feelings rather than her arguments. Juror Seven doesn’t care about the boy’s fate, and votes guilty just to be done with it. In each and every member of the jury, there is some sort of prejudiced view that gets voiced. I myself found that I was inclined to vote the boy innocent after hearing the first argument against his guilt, regardless of all the other evidence against him. This presents us with the several questions that the play is getting at: we think we know who “they” are, but do we really? Is the current system of criminal justice truly just if bias can influence it so heavily? What sorts of prejudice do we bring with us, regardless of where we go? These are the questions that the play wants us to answer for ourselves.

But why does this matter? Why are these the questions LuHi Theater asks us? I think it’s because they are incredibly important. These questions influence how we think. How we view the world. How we view others. They affect how we act. How we forgive. How we hate. They affect the why, the motive, behind each and every one of our actions and views. I think they affect how we see ourselves. What we’re willing to sacrifice so that others won’t have to. I think our experiences and dispositions affect everything about us. I think our sinful natures affect all of these ideas to their core. So, how are they influencing you?